Osteoarthritis is a very common joint disorder affecting over two million Australians, mainly those over 40. Chances are you probably know quite a few people with this condition, and you may even be suffering with this yourself. It is the fourth most common reason Australians see their GP with about half of osteoarthritis sufferers rating their symptoms as moderate to severe.

What is Osteoarthritis?

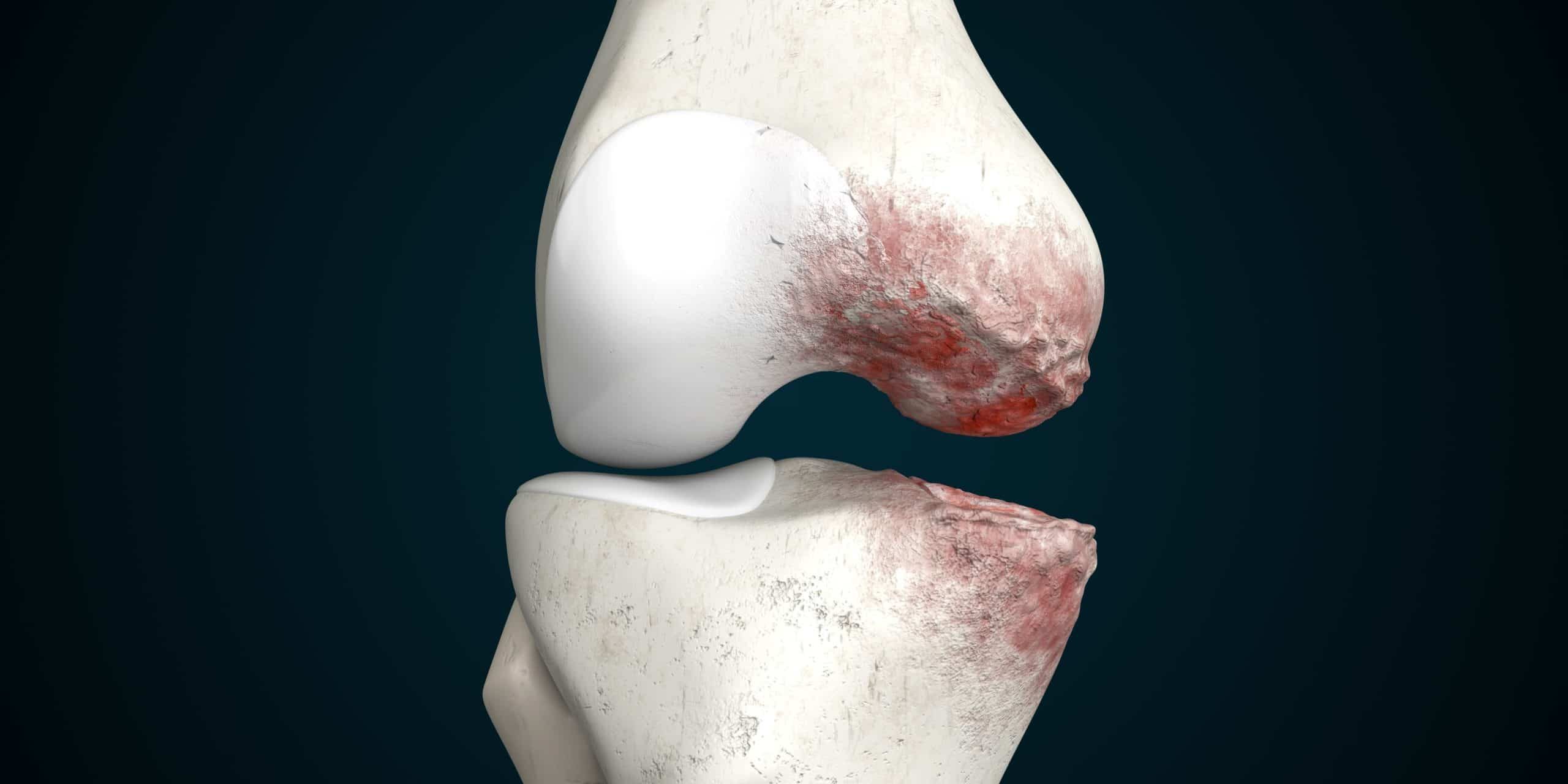

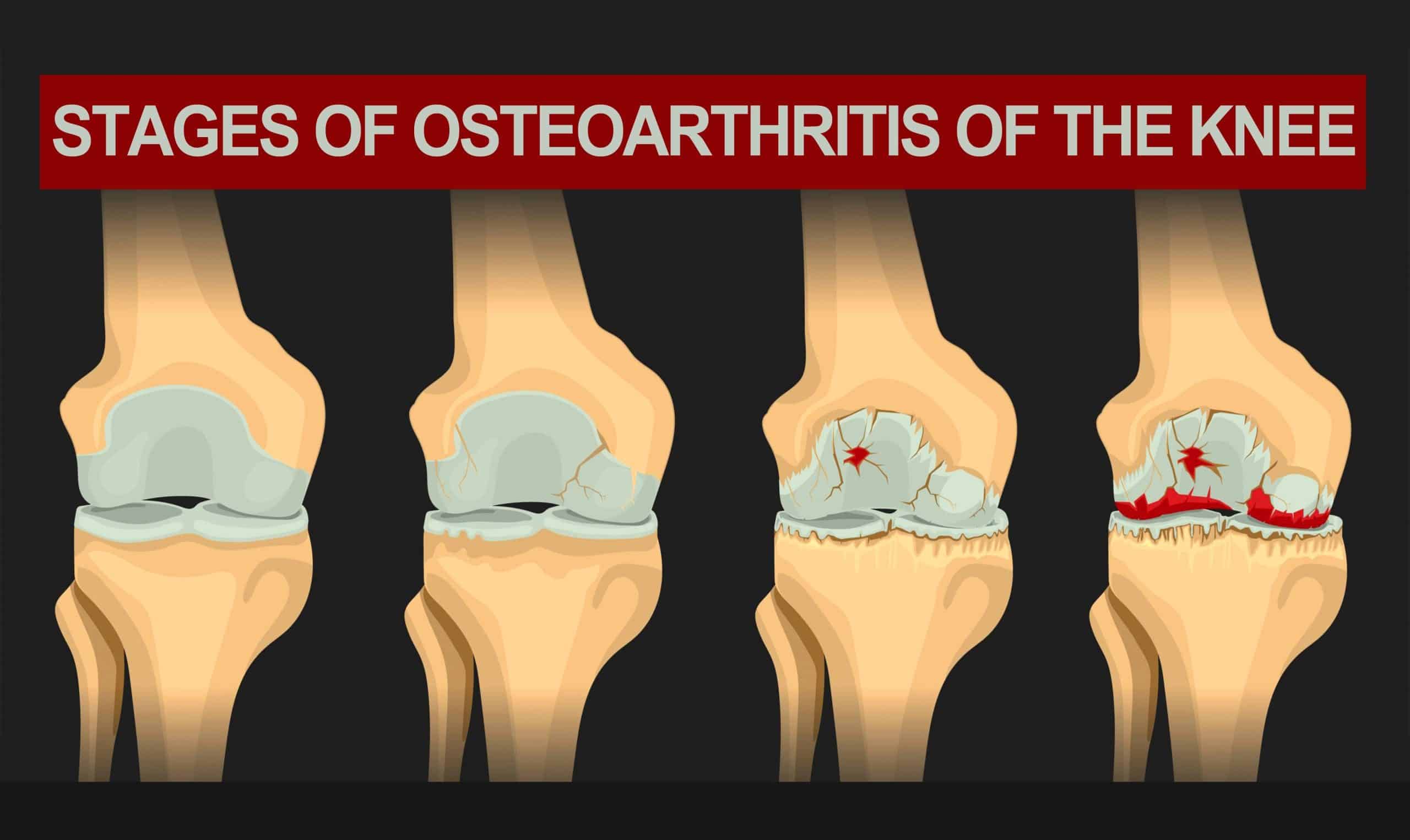

It is best understood as “wear and tear” of the joint cartilage first, followed by collateral damage to the bone and surrounding connective tissues (such as ligaments) as the body tries extra hard to repair itself. This causes cartilage cell death and matrix degeneration through the excessive release of inflammatory chemicals known as cytokines.

Osteoarthritis of the Knee

The humble knee carries the lion’s share of holding us up over a lifetime, sporting an amazing repertoire of running, jumping, bending and twisting, at times under immense load. For example, did you know that one tonne of force is exerted through the patellofemoral joint (between the kneecap and the underlying femur) with every footfall when running downhill? It’s little wonder that knee osteoarthritis is the leading cause of reduced quality of life, amongst all the possible joint disorders.

Common symptoms:

- Pain

- Stiffness (lasting less than 30 minutes after sleep or rest)

- Tenderness

- Swelling without warmth to the touch

- Reduced range of movement

Risk factors for developing osteoarthritis:

- Age. The risk of developing osteoarthritis increases with age.

- Gender. Females, especially after menopause, are at higher risk.

- Obesity.

- Genetics. Roughly 40% of knee osteoarthrosis cases are accounted for by genetics

- Past injuries. Those who have had an injury e.g., a previous anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, are at higher risk of osteoarthritis.

- Dietary factors. Deficiencies in Vitamin C and D may increase the development of osteoarthritis.

Diagnosing Knee Osteoarthritis

This condition can be diagnosed by a thorough history and examination performed by an appropriately trained clinician. An Xray is often also done to confirm the diagnosis.

Managing Knee Osteoarthritis

Non-medication Options:

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has formed a comprehensive management guideline – link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31908163/ – drawn from the best quality research data from around the world. The strongest evidence-based recommendations, weighing the likelihood of benefit relative to the risk of harms, include the following:

- Exercise. This can be walking, specific strengthening, and aquatic exercises including aquarobics. No one exercise is better than another, and the key ingredient is what you enjoy most. Better outcomes are achieved when the exercise is supervised.

- Weight loss if Body Mass Index (BMI) is above 30, and especially if above 35. A realistic and effective target would be a 5% body weight reduction over a 5 month period.

- Tai Chi. A mind-body practice incorporating slow gentle movements with peaceful mindfulness and controlled breathing. It has been shown to improve strength, reduce falls, improve mood and increase self-efficacy.

- Knee brace (tibiofemoral type). It is important that this is prescribed by an appropriately qualified professional, as it can cause harm if not appropriately selected or administered.

- Walking aid (such as a cane or stick) if walking ability or safety is significantly reduced.

Medication Options:

The American College of Rheumatology has the following strong recommendations for managing pain. It is important to note that none of these options actually heal the disease or even slow it down. Your local doctor is a good resource to help you decide if any is appropriate:

- Start with topical (i.e., creams and gels) anti-inflammatories. These can be quite effective in some people and have a lower risk of harm compared to the oral versions.

- Oral anti-inflammatories. These are effective in reducing pain in the short term, but need to be carefully selected based on their side-effect profiles and risk of harm for the individual.

- Glucocorticoid “cortisone” injection into the knee joint. This is often effective in reducing pain over the short to medium term. Careful weighing of the risks is important, as it can thin the cartilage and, should you ever require a knee replacement in the future, it can increase the risk of post-operative joint infection.

Therapies with uncertain benefit or lacking in effectiveness:

There are many popular remedies which have been used for thousands of years. For example, boswellia is still commonly used nowadays for knee osteoarthritis. You may know it better as frankincense, the tapped resin from the Boswellia serrata tree. It is immortalised in biblical passages and Christmas carols, and often associated with gold and myrrh as gifts to Mary and Joseph from the three wise men.

A 2020 meta-analysis of seven studies show that boswellia, especially if it is enhanced with absorption enhancers piperine or bioperine, reduces pain and improves function associated with knee osteoarthritis. However, the scientific rigor of the trials was low, even though they were randomised and placebo-controlled. Bigger and better designed studies are needed before its benefits can be properly measured and weighed against its significant cost and mild gastrointestinal side effects.

Another popular complementary remedy is curcumin, the active ingredient of turmeric. It adds to the spice’s yellow hue, and has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Like frankincense/boswellia, it is poorly absorbed through the gut, and its benefits in reducing pain and improving function appear to be modest at best, and ineffective at worst. It also has significant interactions with some medicines, so do check with your GP before trialling it. Again, the quality of the studies is very limited, and better evidence is needed.

In contrast, glucosamine and chondroitin have undergone good quality studies, which have found that higher doses of higher-grade formulations of glucosamine sulfate (1500mg/day) or chondroitin (800mg/day) have statistically significant (but unfortunately small) benefits compared with placebo. The power of placebo (sham treatment comparator) was impressively demonstrated in the landmark GAIT study, which showed that 60% of blinded participants reported a pain reduction of at least 20%, regardless of whether they were taking placebo or glucosamine/chondroitin!

Unfortunately, under the rigorous methodologies applied by research trials, these therapies do not have enough evidence to be recommended by the scientific and medical community. Let’s continue to watch this space, with non-judgemental curiosity, to see if the benefits (especially when compared to placebo) outweigh the costs and risks of “natural” therapies such as these.

How can we help discover new ways to address this age old problem?

We are pleased to offer two clinical trials which may make a difference:

- One interventional product, when injected under ultrasound guidance into the knee joint space, is designed to tone down the cytokines that degrade and kill off cartilage. This study opens up exciting possibilities for reducing pain, increasing function, and potentially even slowing down the deterioration of the joint. For further information on this trial, visit https://www.austrials.com.au/events/osteoarthritis-knee-injection/

- Another interventional product which, after injection through a very small needle just under the skin, is designed to reduce the sensitivity of pain nerve fibres and the intensity of pain for over a month. For further information on this trial, visit https://www.austrials.com.au/events/osteoarthritis-pain-treatment/